The launch of the new Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow II featured in Motor Sport Magazine in April 1977:

Anything new from Rolls-Royce is significant, even if it is of little consequence to the man-in-the-street. However, the latest comprehensive revisions to the Silver Shadow to produce a Mk. II version, coupled with a price increase of nearly £4,000, are more significant than usual because they reflect an outstanding success story from at least one section of the British motor industry, even if the rest is in the doldrums. What is more, a success story from that paragon of British motor manufacturers, creators of a universal status symbol, can only help the tarnished British image abroad.

David Plastow, Group Managing Director, Rolls-Royce Motors, believes that one of the reasons Rolls-Royces are selling in more numbers than ever before (2,000 cars sold in 1971 rose to 3,261 in 1976, while overseas sales rose from £12 m. to £50 m. in the same period) is that they are no longer just a status symbol. “They are gaining their rightful image as a successful businessman’s tool,” he told us at the launch of the Silver Shadow II in Mijas, in the hills above Torremolinos in Southern Spain.

The Shadow II goes a long way towards confirming this new image : nowadays 60% of Rolls-Royces are believed to be owner driven part, if not all, of the time. The owner-driver is much more concerned with the car’s “driveability” and practicality. It is in “driveability” that this revised Rolls-Royce benefits most from the 1,659 modifications made to it. The most important contribution is the adoption of rack-and-pinion steering, for the first time on a Rolls-Royce, respectability at last for this system. Rolls’ engineers have been considering the use of rack-and-pinion since 1971, but were quite unable to find a suitable unit, or find a manufacturer interested in small volumes. Burman eventually came to the rescue and prototype units have been fitted to test cars for three or four years. This power-assisted rack has its take-off point in the centre, not for innovatory technical reasons, simply to maintain the correct steering geometry, retained from the earlier model.

In addition to the steering changes the front suspension has been modified to give an increased swing axle effect. The idea is to hold the wheel more upright relative to the road when cornering and lower the roll angle. The diameter of the rear anti-roll bar has been reduced to balance the front suspension changes.

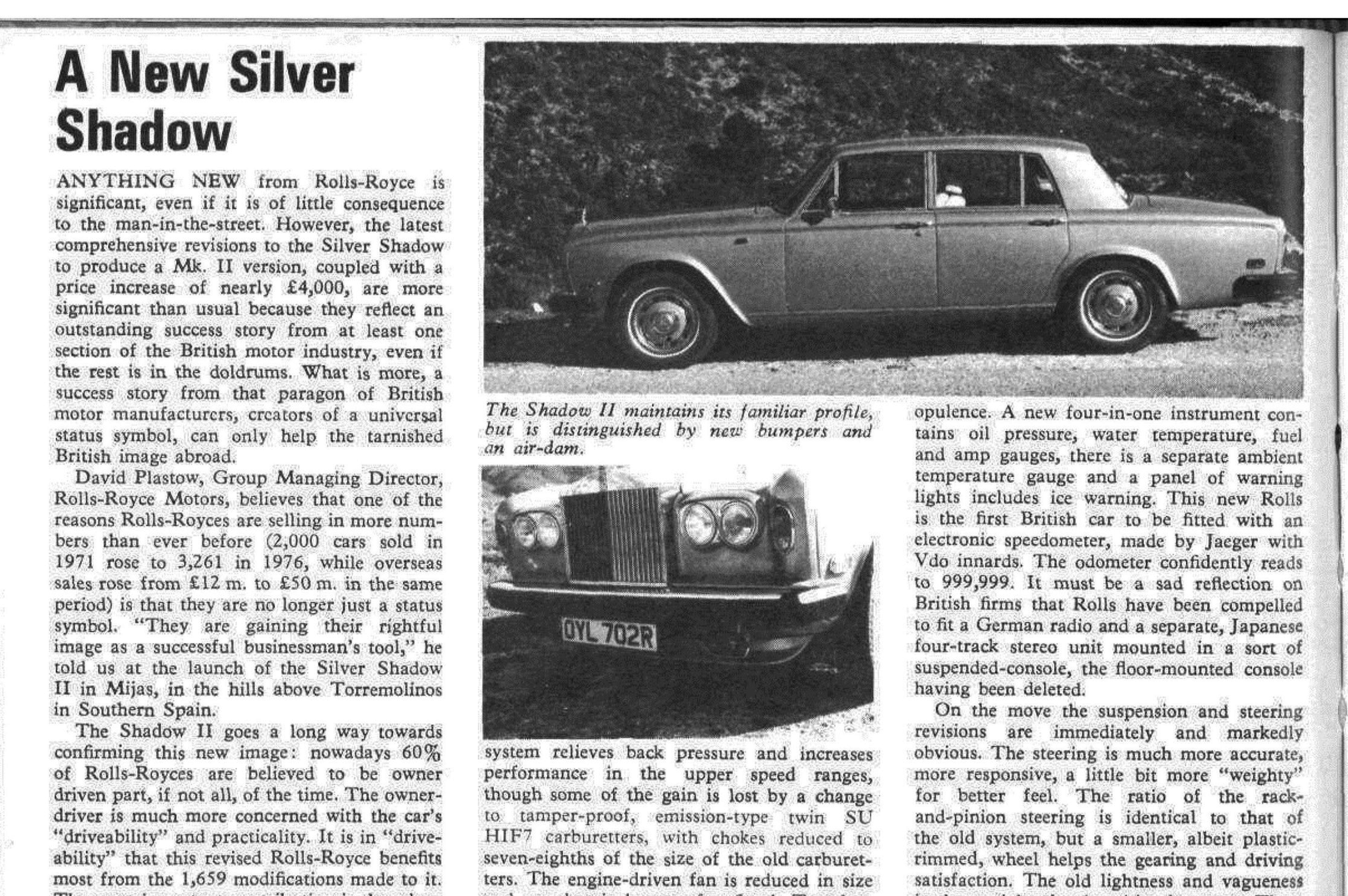

Externally the Shadow II, which retains the familiar, 11 1/2-year-old body shape, is identified by an air-dam fitted beneath the front bumper (really!) and prominent, wraparound safety bumpers. The choice of position for a Shadow II badge high on the boot lid is incongruous. A difference which few will realise is the use of a half-inch-deeper, front-to-rear, radiator grille, previously fitted to American cars only. American Shadow Ils will not be fitted with the air-dam, incidentally.

The sight of twin exhaust pipes at the rear reveals engine changes, too. This dual system relieves back pressure and increases performance in the upper speed ranges, though some of the gain is lost by a change to tamper-proof, emission-type twin SU H1F7 carburetters, with chokes reduced to seven-eighths of the size of the old carburetters. The engine-driven fan is reduced in size and an electric booster fan fitted. Together, these changes should improve fuel consumption by about 10%, an extra m.p.g. perhaps?

A substantial part of the increased cost goes towards the adoption of the Camargue-type, split-level, fully-automatic air-conditioning system, which cost about £1,500 as long ago as Spring, 1975, when the Camargue was introduced (see Motor Sport, April 1, 1975). It is quite brilliant and fool-proof, though I’m still not certain of this complexity’s necessity. Air-conditioning was first offered by Rolls-Royce in 1956 and made standard in 1969.

Rolls-Royce seem to have developed a habit of finding the worst roads possible for testing their new models: the Camargue in the tortuous, rough roads of the Sicilian hills; the Shadow II on the tortuous, rough roads of Southern Spain. The choice was not necessarily a good one, for it revealed creaks and one or two rattles in the out-of-element test car’s heavy body shell, mostly from woodwork and a maladjusted front door. It also disclosed that Rolls-Royce have still some way to go in the search for perfection in tyre and suspension noise insulation, problems which are magnified for their engineers by the sheer weight and bulk of the car. One nameless Rolls-Royce man agreed when pushed that they were still some way behind Jaguar in this respect.

Those familiar with earlier Shadows will find significant changes to the interior. The facia manages to achieve concessions to modernity without detracting from walnut opulence. A new four-in-one instrument contains oil pressure, water temperature, fuel and amp gauges, there is a separate ambient temperature gauge and a panel of warning lights includes ice warning. This new Rolls is the first British car to be fitted with an electronic speedometer, made by Jaeger with Vdo innards. The odometer confidently reads to 999,999. It must be a sad reflection on British firms that Rolls have been compelled to fit a German radio and a separate, Japanese four-track stereo unit mounted in a sort of suspended-console, the floor-mounted console having been deleted.

On the move the suspension and steering revisions are immediately and markedly obvious. The steering is much more accurate, more responsive, a little bit more “weighty” for better feel. The ratio of the rack-and-pinion steering is identical to that of the old system, but a smaller, albeit plastic rimmed, wheel helps the gearing and driving satisfaction. The old lightness and vagueness in the straight-ahead position has gone. There is much less roll, an improvement which is appreciated as much by rear seat passengers as the driver: earlier Shadows, even postcompliant suspension examples, make me feel queasy when an ambitious driver is at the wheel; this one had no such effect on twisty roads. An added bonus to reduced roll, say Rolls-Royce, is that wear on the tyre shoulders is minimised. The combined effect of the modifications made this big Rolls quite surprisingly enjoyable in the difficult Spanish conditions. It could be cornered with much more confidence, understeering to a safe and stable degree, with no little quirks in mid-corner. Traction felt to have benefited too. The excellence of the brakes, the surprising performance of the big, far from inaudible V8 and the smoothness of the GM automatic gearbox goes without saying.

The steering and suspension revisions have been adopted in parallel on the Comiche and Camargue. They should make the Crewe marque a much more desirable asset to the owner-driver than previously. At the same time the Bentley name has not been forgotten and a Mk. II version of the T-series is available for the same price as the Silver Shadow II: £22,809. David Plastow revealed that an increase in Bentley production is planned and the marque promoted through the dealers. He even went so far as to say that while his company would never produce a cheaper model, “Many years from now might see us do something up market with Bentley.” W.O. would be pleased—CR.

Source: Motor Sport Magazine (https://www.motorsportmagazine.com/archive/article/april-1977/34/a-new-silver-shadow)